About 150 women report being raped to the police in South Africa daily. Fewer than 30 cases will be prosecuted, and no more than ten will result in a conviction. This translates into an overall conviction rate of 4% – 8% of reported cases. In this edited extract from her book, ‘Rape Unresolved: Policing Sexual Offences in South Africa‘, DEE SMYTHE, Professor in the Department of Public Law at UCT, explores why this is the case.

One story

It is a warm Friday evening in Masiphumelele, a settlement in the far south of Cape Town. On her way home from work, Tandazwa Mpofu (not her real name) stops for a quick drink at a shebeen, one of the tens of thousands of vibrant, informal (and often illegal) drinking establishments found across the country. She phones her sister to join her, but she’s still working.

She takes a chair outside at the shebeen – it is summer, still light, and already getting hot and stuffy inside. A woman invites her to join their table. She introduces Tandazwa to a man she says is her father. An hour or so later, when Tandazwa says goodbye, they offer her a lift home. The car is distinctive: souped up in a backyard, painted red, with black racing car stripes down the sides.

After dropping off his “daughter”, the man takes Tandazwa to a quiet road, where he rapes her at knifepoint and throws her out of the car. Naked, she finds her way to the house of a friend, who gives her clothes and takes her to the police station. She can identify the car and is confident she can identify the man who raped her. Many other people at the shebeen saw them together. She can identify the man’s “daughter”.

One month later, the only entry in the police docket is a short summary of the facts, written by the detective, with the following phrase underlined in red:

… he bought beers for the victim …

Nothing else has been done to pursue the investigation. The docket goes to the Detective Commander for inspection. Obviously angry, he writes in the investigation diary:

Your investigation or the lack thereof comes down to severe negligence on your part. This docket must receive the attention it deserves. Why was no crime kit completed? Do it NOW!

That same day the detective goes to the victim’s house and obtains the following withdrawal statement from her:

I have spoken to the investigating officer about the case, but I cannot answer any of his questions. That is, who is the man who raped me, who was sitting at the table [in the shebeen], and also where it happened. I can therefore provide no information to take this investigation forward. I also told my mother this. I therefore feel like I don’t want to continue with the matter.

The case is closed, marked:

… withdrawn complainant.

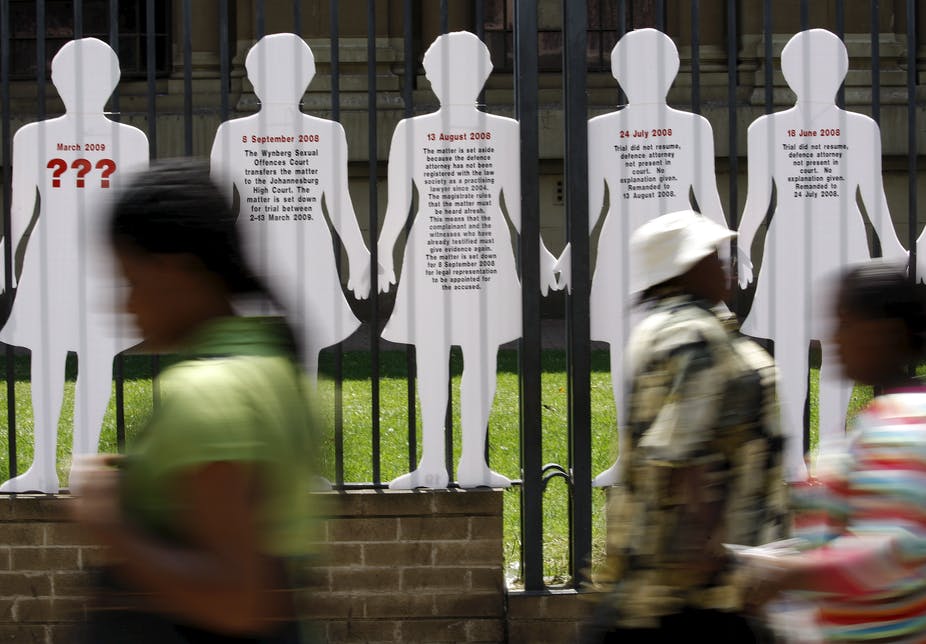

Attrition

A quote from former Western Cape Provincial Police Commissioner Mzwandile Petros:

On a Friday and Saturday you have long queues of people reporting crimes against women and children, and then on Monday you have a long queue of people wanting to withdraw these cases … I am concerned as the Commissioner of Police about the conviction rate of these cases … If I have a 1% conviction rate, I have to be concerned about it.

For various reasons, attrition happens in the criminal justice system, so not all reported cases are prosecuted and not all prosecuted cases result in a conviction. But the view expressed by the provincial Police Commissioner and the experience of Tandazwa Mpofu reflect two very different perspectives on attrition.

In both instances – the woman who withdraws her complaint on Monday morning because she has sobered up or reconciled with the perpetrator, and the woman who withdraws her complaint because of police incompetence and apathy – the official outcome written on the docket and captured in police statistics is the same: “withdrawn complainant”. But the locus of responsibility for that decision and the degree of agency exercised by the victims differ markedly.

While attrition is expected in any functional criminal justice system, it occurs in an institutional context that is shot through with discretion. One scholar has gone so far as to suggest that

… (w)hat we call the criminal justice “system” is nothing more than the sum total of a series of discretionary decisions by innumerable officials.

The actions of criminal justice actors and their decisions are crucial parts of the attrition story.

The police decide whether to open a case, investigate it and how much effort they will put into accumulating evidence and finding the perpetrator. It is their choice (whether they recognise it as such or not) to encourage a complainant in her efforts to bring the perpetrator to justice or to acquiesce in her withdrawal from the justice system. The police decide whether a case should be referred to the prosecution.

Prosecutors decide how to frame a particular set of facts as an offence – shaping a fit between what they can prove happened and elements that define the conduct as criminal. They decide whether a case has sufficient merit to be taken to court, what evidence will be brought, and who will be heard.

And ultimately, a judge decides whether the state will provide redress.

Throughout this process, manifested at crucial decision points, cases leave the criminal justice system. In this way, criminal justice actors have the power to select those whom the state will protect, who will be put on trial, and who will obtain justice.

Stereotypes of what constitutes rape

Scholars studying attrition in rape cases generally explain the low rate of reporting and conviction in these cases by pointing to the stereotypical views held by criminal justice actors about what constitutes a sexual offence and who can validly claim to have been victimised.

They argue that these beliefs have become scripted into criminal justice practice. The result is that the cases filtered out of the system are not intrinsically weak but rather those that offend the normative assumptions of decision-makers.

There is empirical support for this contention. Studies conducted over the last 40 years have shown that the closer the fit between the facts of the rape reported and the decision-maker’s conception of what constitutes “rape” (as opposed to “bad” or even “normal” sex), the more likely it is that the case will proceed successfully through the system.

On this account, “violent” rapes committed by predatory “strangers” against “respectable” (for which read white, middle-class, married or virginal) women, who are injured while resisting, have become the paradigm cases against which all rape reports are measured in the criminal justice system.

Complainants who are perceived to have precipitated their own victimisation, whether through their conduct or their relationship with the perpetrator, are at a particular disadvantage.

Being drunk (or accepting a drink from the alleged perpetrator), hitchhiking, flirting or selling sex all diminish a complainant’s credibility and the validity of her claim on the criminal justice system, even where there is evidence that the accompanying sexual acts were coerced.

Despite evidence that intimate-partner rapes are among the most violent manifestations of sexual violence until relatively recently, most jurisdictions have regarded marital rape as a contradiction in terms and provided little protection to women who are raped by their husbands.

The residual effects of centuries of prejudice linger tenaciously in criminal justice canons of sexual violence, relentlessly reproducing unjust outcomes at the same time as they produce our very conceptions of sex and sexuality. Cultural beliefs about women and sex, and the notion that what women really want – what they find romantic or erotic – is to be overwhelmed by male sexual aggression, infuse “common sense” social and legal opinion, often leaving victims of rape without recourse or protection.

Numerous studies have unmasked examples of misogynist stereotyping within police ranks, with experts suggesting that the institutional character of policing, with its own peculiar set of norms and stereotypes – machismo, cynicism and scepticism being not the least of these – makes the police particularly unsuited to dealing with victims of sexual violence.

Police’s story

The police tell a different story. At least, in South Africa, they do. Theirs is a tale of uncooperative victims. It is the Police Commissioner’s indignant comment about long lines of complainants on a Friday and Saturday night waiting to report crimes of violence against women and equally long lines on a Monday morning wanting to withdraw their complaints.

Police talk about complainants who cynically use the criminal justice system, fabricating or exaggerating rape complaints to further their own instrumental goals – of revenge or extortion, mostly – or explaining their sexual misdemeanours.

The police argue that even when they are sympathetic and helpful, many victims withdraw valid complaints, refusing to cooperate in the investigation and prosecution of the aggressor. They say that an inordinate number of rape complaints are false and suggest that in specific communities, this has become a common means of exacting revenge on male partners (past or present).

Furthermore, substantial numbers of rape complainants withdraw charges once they or their families have received financial compensation from the perpetrator.

And finally – to a lesser extent, although very prevalent in specific areas – direct or indirect intimidation forces complainants to withdraw charges.

These police officers have been through many hours of sensitivity training. They can reel off the ten biggest rape myths, and they care about bringing rapists to justice; but they maintain that if complainants do not cooperate, there is little that can be done to pursue the case.

Their discontent runs along the following lines: investigating rape complaints is often a frustrating waste of time. The effort required to investigate those cases must be weighed against other urgent organisational pressures and priorities, particularly in a resource-constrained environment like South Africa. They argue that South Africa is fighting a “war on crime”, and the police are the vanguard. If rape victims are not serious about their cases, they have only themselves to blame if they don’t get justice.

Some argue that complainants should not be allowed to withdraw their complaints at all; and that if they insist on doing so or recant, they should be charged with defeating the ends of justice. The overarching claim is that it is complainants and not criminal justice actors or actions that are responsible for the closure of cases.

Victim recalcitrance and systematic failures

In the mid-1990s, the South African government responded to the pressing problem of sexual violence by making violence against women and children a strategic crime prevention and policing priority.

Translation of this rhetorical commitment into effective programmatic interventions has never been fully achieved. Nonetheless, the commitment to it is constantly reiterated in law and policy and through the courts.

The stories I collected in my research reflect evidence of both victim recalcitrance and systemic failures. They cannot be neatly parsed. A picture unfolds of attrition as deriving from the complex interaction of individual, structural and systemic factors.

While it is likely that the factors identified in my research share similarities with those of other, more developed countries, it is also arguable that many of them – and how they combine – are reflective of the social and institutional dynamics of a developing country, and even more specifically, of the transitional post-apartheid South African milieu.

Why the blame game is unhelpful

Simplistic accounts of uncooperative and prevaricating victims on the one hand, and unsympathetic misogynist cops on the other, do not take us any further towards understanding the dynamics of rape attrition.

If the police are correct in their estimation, we are dealing with tens of thousands of deceitful women placing an intolerable strain on the system and its minimal resources.

If women’s-rights activists are correct, the police remain deeply and irredeemably misogynist in culture and practice. When nine out of ten reported cases are not prosecuted (and two out of three are not even referred to the prosecutor for a determination), we are faced with a massive systemic failure that needs to be understood. When the numbers are as substantial as in South Africa, the problem becomes urgent.

Therefore, understanding this phenomenon is at the centre of identifying ways to strengthen and develop police and civil society interventions and effect meaningful access to justice for victims of sexual offences.

Rape Unresolved: Policing Sexual Offences in South Africa by Dee Smythe is published by Taschenbuch.

This story was first published by The Conversation Africa.