How do we think and practice genuinely universal solidarity when some wars and conflicts are met with a searing silence? asks Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung.

“Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable. This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.

Gabriel García Márquez – The Solitude of Latin America

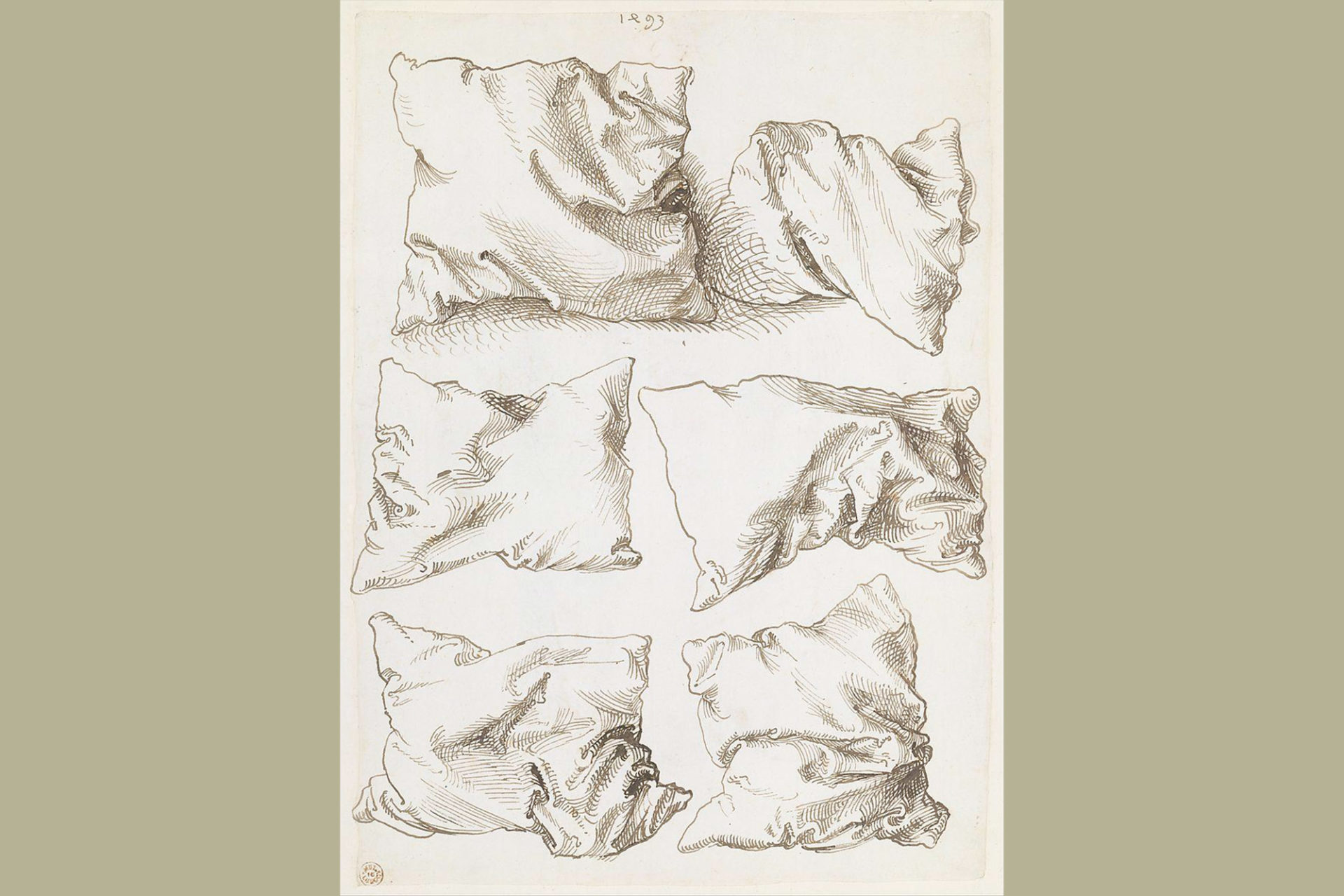

Since Russia’s violent invasion of Ukraine a few days ago, I have found myself – like many others, I assume – restless by day and even more by night. When the birds settle in for their slumber, and the crickets stridulate, and other insects proclaim and celebrate the night with their chirps and other creaking noises, I have found myself unsettled, turning over, churning and kneading my pillow all night long. At the break of dawn, my pillow looks like it metamorphosed through the various stages of Albrecht Dürer’s Six Studies of Pillows (verso) from 1493. And as I look at the facets and contours, the twists and turns, the rough waves and tides, and Dürer’s clean hatchings, I wonder how Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy’s pillow must look after all these nights of bombings. I wonder about the unease of sleep and sleepless nights that the people of Ukraine have gone through in the past nights, tumbling across and biting teeth into their pillows with each strike. And I think of the many innocent Ukrainian people – daughters, sons, sisters and brothers, friends and relatives – that have been going for nights without pillows in metro stations and bunkers. So my solidarity with, sympathy for and support of the Ukrainian people as they go through these unbearable times.

In the past days, friends within and out of my art circles, artists, colleagues, students, and many I am not acquainted with have asked me to make a public statement and sign or share letters in solidarity with Ukraine. While I have shared my solidarity with them, I have made it a point, just as I have done in the past years when contacted regarding other conflicts, that solidarity is not a one-way street; solidarity must be multidimensional and multidirectional, solidarity is not coloured white and must also apply to the “darker than blue” of the world, and solidarity cannot be a racialised notion or practice.

Solidarity with whom?

This call for solidarity, especially in support of Ukrainians trying to leave the country to get into Poland and other neighbouring countries, is very timely as children, women, and men are in dire straits. But what is most baffling is that in the height of winter, just a few weeks ago, thousands of people fleeing from war in the Middle East were also trying to cross these same borders into Poland and were beaten up, maltreated, shot at by the border police. At the same time, many were left to die in the cold. None of the many colleagues and friends writing to me today, and very few in my inner circles, showed concern for the fate of the Middle East refugees, and none started a solidarity movement for the Syrian, Yemeni or others while the people were stuck at the border. Do Middle Eastern women and children not deserve as much refuge and solidarity as other humans in need?

As I write, news and videos are circulating on social media showing hundreds of the more than 30 000 Africans in Ukraine who are trying, too, to leave the country. The only difference is that while the world is uniting in solidarity with Ukraine, the Ukrainian army and paramilitary are stopping the Africans, South Americans and Caribbeans from boarding the trains. It is said that priority is given to Ukrainians.

A note must be made here that by Ukrainians, they mean white Ukrainians, as many of these Black people also carry Ukrainian citizenship. According to witness reports, the Ukrainian military has pointed out that they prioritise the escape of children and women. Still, at the same time, they have stopped Black women and children from taking the trains. As it were, some Black people who succeeded, after enormous insistence and pressure to get on the trains and buses, are being hindered by the Polish border control from getting into the country. Solidarity doesn’t seem to be blind but seems to discriminate along colour lines. Solidarity itself appears to have a colour, and it is not Black. Unlike the discriminate solidarity we are observing unfold in this drama, the bombs dropped by the Russian army in Ukraine are indiscriminate, know no skin colours, know no racial denomination – the bombs just kill.

Cameroon, my country of birth, has been in a ferocious war; at least the “anglophone” part of the country from which my family comes has to a large degree become a no-go area for many. Thanks to this war, I saw young and old kidnapped, children and women cold-bloodedly murdered by the government troops and the Ambaboys. My parents, in their 70s, had to go on exile, where my father eventually died. As Henry Bang and Roland Balgah point out, this conflict has led to the displacement of over 1.3 million anglophone Cameroonians – internally displaced persons and refugees to neighbouring Nigeria. In some villages, more than 80% of the inhabitants have escaped into and now live in the bush. In five years, some villages have become completely deserted and reduced into ghost spaces. The casualties in this crisis are anywhere between 4 000 and 15 000 civilians.

I have written about this widely in essays and talked about it in lectures and numerous posts on social media in this regard. In the particularly crass human rights violations like when the government’s security forces, besides its excessive use of force, torture of suspected separatists and detainees, also burnt down houses of anglophone people in more than 170 villages, including the massacre of 21 unarmed civilians in Ngarbuh village of the North-West Region of Cameroon on 14 February 2020.

In that same year, on 24 October, young men, presumably Ambaboys, stormed a school in Kumba, in the South-West Region, with guns and machetes, and while filming, killed seven children of 12 to 14 years and injured more than 13. After these atrocities, I hardly saw any indignation from the same people now calling on me to show solidarity, nor did I see anyone hoisting the flags of Cameroon or Ambazonia on their Facebook walls. I am waiting for just one of my liberal art friends and colleagues, primarily discourse-leftists, concerned with the world and ready to protest against the environmental crisis, to write to me asking for my solidarity with and support for the people of anglophone Cameroon. And as I wait, I am forced to ponder if, after more than five years of war, the people of anglophone Cameroon are not receiving the same solidarity as our European brothers and sisters because they are too far away, not white enough, too Black, or just not human enough to receive the same solidarity?

Some lives seem to matter more

As for the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), we seem to have all stopped counting the number of people killed in the manifold conflicts that have engulfed the country in the past decades. In the larger scheme of things, the life of a young person in Congo might just as well be as worthy as the life of a summer fly smacked on a wall. But as the Global Conflict Tracker informs us, the United Nations estimates there are about 4.5 million internally displaced persons in the DRC and more than 800 000 DRC refugees in other nations. Though the second Congo war officially ended in 2003 and is said to have cost 5.4 million lives, it is said that a few additional millions have gone down since its official end. Despite these alarming figures, not even the US-initiated Black Lives Matter movement has a headache when thousands of people are killed in Congo. Some lives matter more than others; some Black lives are more worthy than others.

In 2015, after the cowardly terrorist attacks on satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo that left 12 people dead, the French president, François Hollande, called for global solidarity. These 12 French lives carried enough weight to pull 60 world leaders to Paris, where they marched with large crowds to show their indignation against terrorism. Among these 60 leaders were former prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu of Israel, Germany’s former chancellor Angela Merkel, former European Council president Donald Tusk, Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, Mali’s former president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, and several other African leaders.

The value of the Black African lives can be measured in times of crisis, especially terrorist attacks, as for several years now, we have seen terrorist attacks in Mali, Cameroon, Nigeria and many other places, but never have we seen a roaster of such leaders come to show solidarity – not even the African leaders, not even when their kind are killed, because, in the colonial mindset, the lives of people in Paris are more valuable than the lives of their own people. Some lives seem to be more equal than others.

To whom do we owe solidarity?

Who deserves our solidarity?

Which lives are worth showing solidarity for and with?

Which books should we read, which flags should we hoist, what solidarity statements should we all share online on social media when thousands of people from the African continent and the Middle East drown in that vilest grave of modern times, the Mediterranean sea? What colours of indignation should we wear, what songs of lamentation should we sing and in what language, what will be the taste of our tears – salty or sweet – when thousands of people drown in that Mare Nostrum, the Mediterranean Sea?

Sometimes I wake up from a nightmare, sweaty and cursing that 100 cats had drowned in the Mediterranean Sea and people had filled the streets of Europe, and the European Union had declared three days of mourning.

Finding a place to rest

When Russia launched this war on Ukraine, I was in Martinique on a research trip combing through the repercussions of the 600-year long European-initiated transatlantic slave trade that saw the abduction and displacement of millions of Africans to the Americas. Many millions never reached the other shores of the Atlantic as they died of the brutal conditions of transportation or were wilfully dumped off the ship, as was the case with the Zong massacre of 1781. The dismal realities of this enterprise that was enabled by and had as a consequence the dehumanisation of people still live on. This genocide of most alarming proportions is something we have learned to take for granted as we walk through plantations, through distilleries, visit colonial churches transformed into cultural centres in whose gardens the most beautiful roses and other tropical plants grow. It is frightening to see just how beautifully, exquisitely, and sumptuously roses can blossom when they are watered with the blood of the enslaved while growing on the decaying carcass of the enslaved.

In Martinique, my colleague Raisa Galofre read out loud to us the acceptance speech of the great Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez. Evoking the master William Faulkner who said, “I decline to accept the end of man,” Marquez went on to add: “Faced with this awesome reality that must have seemed a mere utopia through all of human time, we, the inventors of tales, who will believe anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of the opposite utopia. A new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true, and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to 100 years of solitude will have, at last, and forever, a second opportunity on Earth.”

This statement left me shaking. It brought me to the simple and maybe banal realisation that the wars in Ukraine, in Tigray, in the north-west and south-west Cameroon, in Yemen and Western Sahara have in common the inheritance of a necro phantasm. They bear the heritage of cultures in which the weapons industries thrive more than the hospital or food industries. Death is the fuel that drives the machinery of neoliberal socioeconomic systems that privilege death itself over life. More than 600 years of dehumanisation and othering have thrust some humans into the solitude of existence. It is not a self-chosen but an imposed solitude – not within themselves per se, but from those who have historically been the ones to disenfranchise others and who still have the leverage and call the shots on who deserves or does not merit solidarity.

But to affirm solidarity is to privilege life over death. It is to negate the possibility of some to decide for others how they should die; to affirm solidarity is to create structures, networks, fertile grounds on and within which love will prove true and happiness must be possible. Affirming solidarity ensures that the races condemned to 100 years of solitude will immediately and long-lastingly have their due opportunity on Earth. Or to put it in Marquez’s words again: “Despite this, to oppression, plundering and abandonment, we respond with life. Neither floods nor plagues, famines nor cataclysms, nor even the eternal wars of century upon century, have been able to subdue the persistent advantage of life over death. An advantage that grows and quickens: every year, there are 74 million more births than deaths … a sufficient number of new lives to multiply, each year, the population of New York sevenfold. Most of these births occur in the countries of least resources – including, of course, those of Latin America. Conversely, the most prosperous countries have succeeded in accumulating powers of destruction such as to annihilate, a hundred times over, not only all the human beings that have existed to this day but also the totality of all living beings that have ever drawn breath on this planet of misfortune.”

Solidarity is only solid and worth the name solidarity if it goes out and beyond its comfortable premises and embraces those that have been banished to the solitude of existence. Solidarity is only worth anything if we accept, cultivate and propagate what Amitav Ghosh calls in The Nutmeg’s Curse, the politics of vitality – and not only for ourselves but all kinds and species on the blessed planet through which we are just passing.

In the short time in which we all accommodate this space called Earth, and in which we walk on and feed on the gifts of its soil, all we want is to be able to – with our families, friends, and even foes – find a pillow to lay our heads on and find rest. If we cannot ensure that those trying to cross the Sahara or the Rio Grande or the Mediterranean Sea or otherwise can find a pillow to rest on, we will never find peace, for solidarity is the utmost means to render our lives not only believable but also liveable.

This article was first published in New Frame.