From access to global trade to its ability to feed a rapidly growing population, agriculture in South Africa faces a crisis unless it undertakes safe and sustainable environmental practices.

Dr Sean Moore, of Citrus Research International, was one of three keynote speakers at the launch of the Centre for Biological Control based in Rhodes University’s Department of Zoology and Entomology.

He cited UNICEF figures that show Africa’s population, around 1.2 billion in 2014, will double to 2.4 billion by 2050. More than half of South Africans are at risk of experiencing hunger, according to Oxfam – but the challenge for agriculture to feed a growing population goes beyond our borders, with sub-Saharan Africa predicted to have the highest rural population in the world by 2050 and projected to contain 21% of the world’s population by 2100.

For the sake of human health and sustainability, and because it’s cheaper and quicker, than synthetic chemical pest control, biocontrol of crop pests will be key to making this possible, Moore said.

Even large-scale commercial farmers who could afford to buy manufactured pesticides would be forced to adopt biocontrol measures, as global markets demand safe food produced in an environmentally sustainable way.

Moore predicted that by 2063 biocontrol will be a highly lucrative industry, outstripping the use of synthetically manufactured chemical pesticides.

His presentation to a packed Barratt Lecture Theatre included figures demonstrating that with turnovers up to 150 times those in the agrichemical industry, retailers had long been calling the shots.

“With the globalisation of the agricultural trade, farmers must provide what the market wants,” Moore said. He said the European Union set the trend in environmental safety and commercial farmers hoping for a share in that very lucrative market would be forced to replace dangerous chemical pesticides with safer control methods.

Because chemical pesticides disrupt endocrine function in people, and cause cancer, European retailers now insisted on minimum residue levels of chemicals, Moore said. With the promise to their markets of ethically and safely produced food, this was no longer just a safety requirement, but a condition of trade.

Biocontrol is the use of a plant’s natural enemies – insects, parasites and diseases – to reduce its population. In South Africa it’s used to control water-hogging invasive alien plants, as well as for pest control on agricultural crops.

Deputy Director General of the Department of Environmental Affairs Dr Guy Preston, representing Minister Edna Molewa at the launch, described invasive alien plants in southern Africa as “a catastrophic threat”.

Preston, along with former Environment Minister Kader Asmal, pioneered the Working for Water programme to remove invasive alien species while creating jobs and developing skills. Around 300 Working for Water projects are based in communities around South Africa.

Water-scarce South Africa already uses 98% of its available water resources and now is struggling under a critical drought. A large invasive alien tree, such as the bluegums recently removed from Waainek, is estimated to use between 100 and 1 000 litres of water a day – considerably more than indigenous vegetation.

Preston explained why the Centre for Biological Control, with its 35 staff – many of them with disabilities – was a particularly strong candidate for government and other funding and support. He used the Department’s environmental programmes to illustrate an approach to research that addressed both scientific requirements and community needs.

“If you think we can fund a project without addressing poverty, then please don’t get into fundraising,” he said bluntly.

South Africa’s junk status could see R100 billion leaving the country, Preston said, and any entity looking for funding had to have a strong case.

Like other speakers, Preston spoke of the extraordinary vision, skill and social intelligence of the Centre’s driving force, Director Professor Martin Hill.

“I have absolutely no doubt that the Centre for Biological Control is one of the best investments we have ever made,” he said.

Professor Cliff Moran, Emeritus Professor from UCT, Rhodes Vice Chancellor Dr Sizwe Mabizela and Hill himself also spoke at the launch of the prestigious Centre.

Protecting biodiversity

The Centre for Biological Control in the Department of Zoology and Entomology is built on the foundations of the Department’s Biological Control Research Group.

For nearly 45 years, biological control activities at Rhodes University have been the domain of an informal association of teachers, researchers, students, administrators and other support staff. For the past 14 years, the Centre has attracted significant external funding, and generated a high scholarly output.

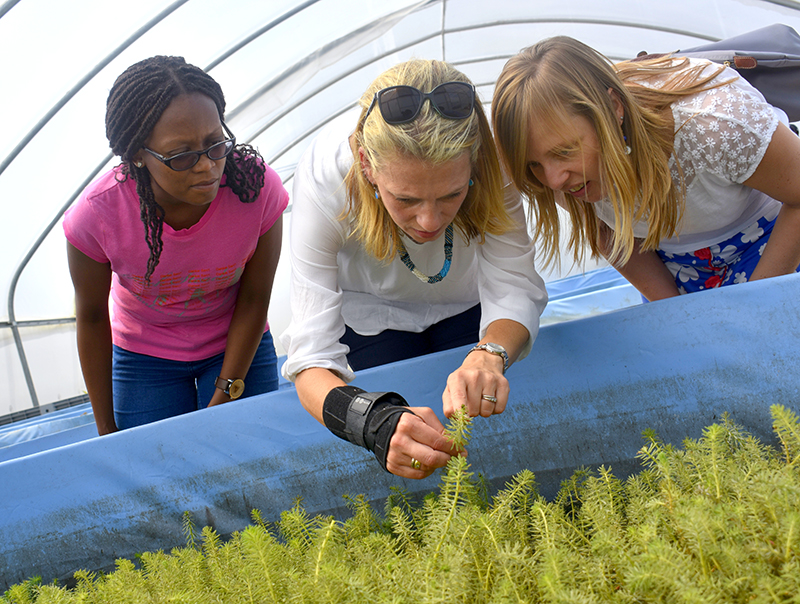

The Centre houses two Mass Rearing facilities, at Waainek and in Uitenhage. It also houses a Quarantine Facility for research into potential biological control agents.

The facilities cultivate invasive alien plants in controlled greenhouse environments, which in turn are used to culture the biological control agent specifically approved for control of that plant.

The agents are eventually released at recognised and monitored invasive plant populations across South Africa. These biological control agents are available free to researchers, implementation officers, reserve and water quality managers, farmers and concerned members of the public who want to get involved in preserving biodiversity and controlling invasive species in their local natural environments.

Biological control agents mass reared by the centre are approved for safe release in South Africa by the regulatory bodies; the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and the Department of Environmental Affairs and conform to current legislation.

The identification and control of invasive species is a continuous and ever-evolving problem.

Every year scientists and farmers identify more species as problematic and new biological control agents have to be found.