By TERESA WILLOUGHBY

6 pm to 6 am. From 20˚C to 4˚C. These are standard working conditions for Lubabalo Mtunzi more than three times a week. With teeth shining, the security guard laughs as I stand shivering at his post alongside the Nelson Mandela Dining Hall, waiting for him to finish jotting down his hourly observations.

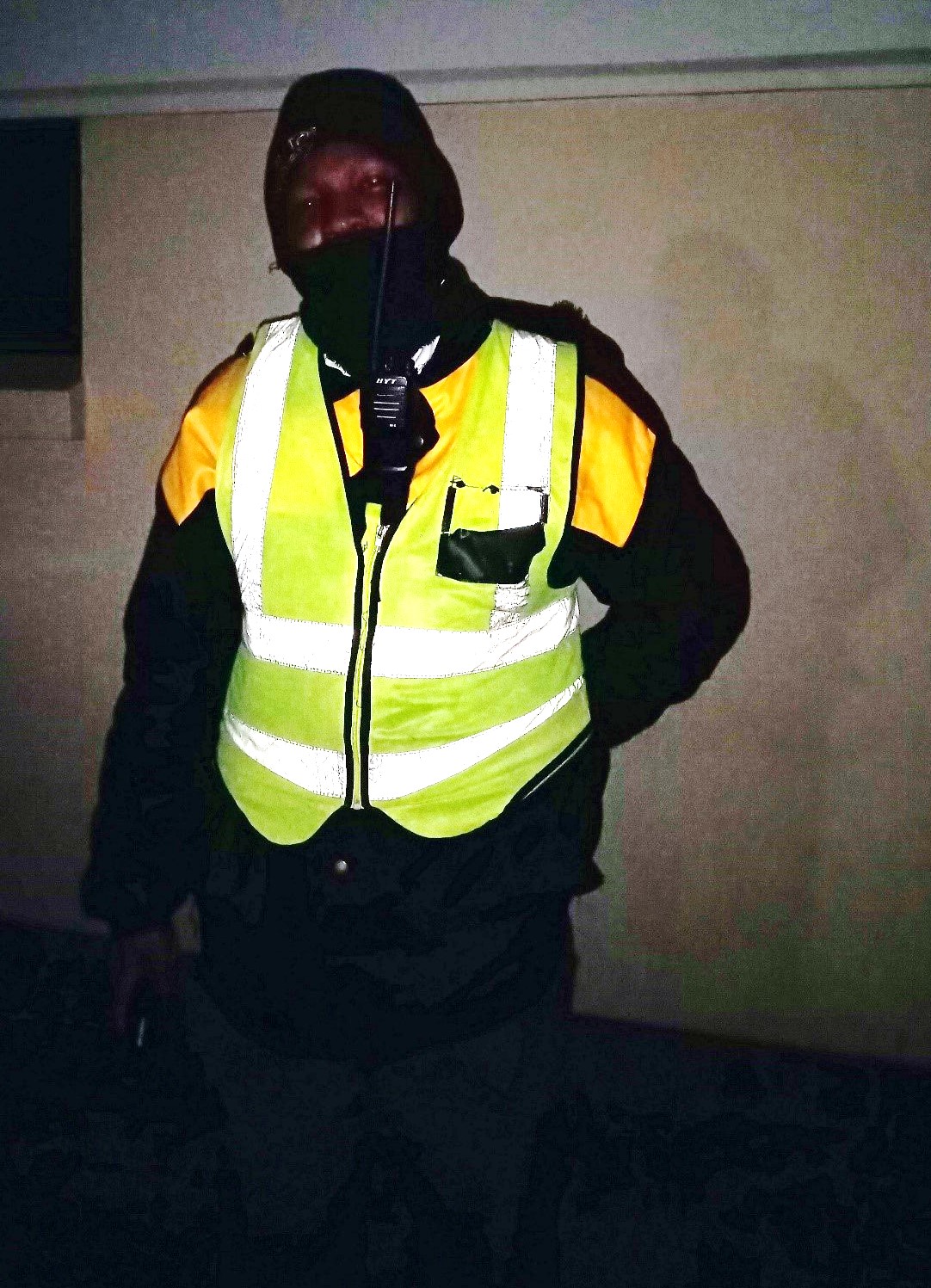

After a chuckle directed at me, he tells me I need to understand how to wear warm clothes. He proudly flexes his foot, exposing the long tights he had just added to his uniform. Learning from a previous mistake, he predicted that the provided uniform – thin pants and the black and yellow jacket – was insufficient to take him through the night.

Once the jottings are complete, he rushes through his words, excited to start the following sentence as he expresses the joy of being a Hi-Tec officer. The joy comes from knowing there will be a pay-cheque at month-end rather than stories of where the money might have gone.

Mtunzi has no problem dealing with the chaos of being surrounded by student life. His parents prepared him for the weight of life, and this job has aided him in his quest to start on his own. As we talk in the cold night, he reminds me to make sure that I learn all my parents have to teach when it comes to living in this world.

He also says that working as a Hi-Tec officer has given him a better understanding of students and student life. “You drink alcohol when you have time, and when you drink, you drink to be drunk,” he says.

From the depths of his pockets, he pulls out a big black, brick-shaped device, holds it up to the light and smiles. The black device is a panic button for when student life gets too dangerous and backup is needed. He reassures me that the guys in the main office don’t play and that I am always safe on campus.

It is time for round four of the hourly observations. As Lubabalo Mtunzi heads back into the dark and cold, I turn towards the warmth of my bed – surprisingly warmed by the conversation.