By JENNA KRETZMANN

Every year the National Arts Festival becomes a mad microcosm reflecting the state of our nation. And yes, this also happened during our two years of virtual engagement. Our artists, having absorbed all the collective issues, heartbreaks, frustrations, and joys, have cogitated and wrestled them into forms we can recognise, presenting them to us in ways that make us see them and ourselves from a different angle.

Legendary for its diverse programme, the festival is a platform where freedom of expression is exercised, stretched, and celebrated. Our artists, battered and bruised – some of them broken – by an uncaring government, public and corporations that far too often take them for granted and the hammer blow of lockdowns that shuttered their lifeblood overnight, have continued to break boundaries, challenges ideas and unearth dormant discussions. They are our coal mine canaries and our lighthouses, disturbing the comfortable and comforting the disturbed.

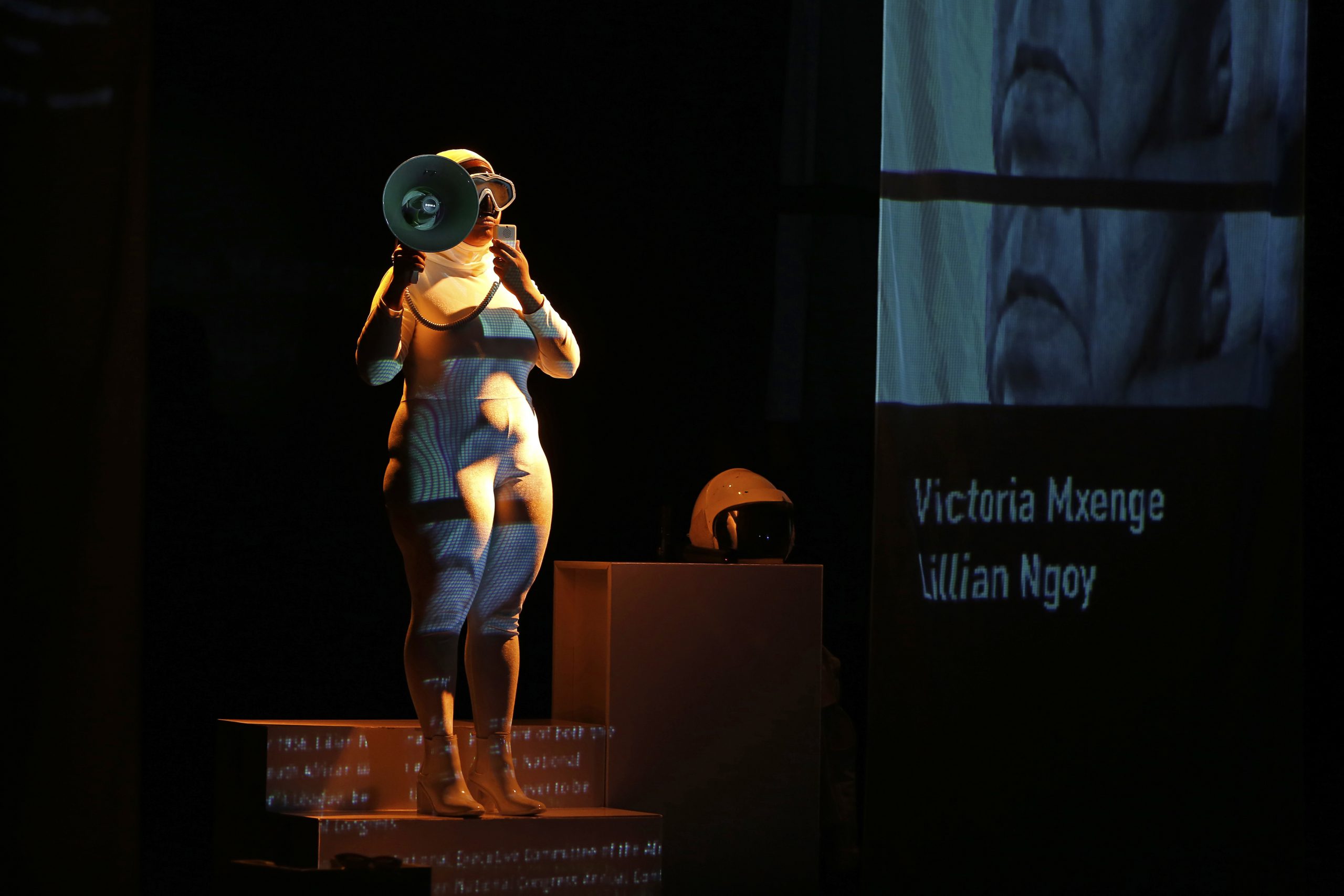

Non-surprisingly, one of the most prominent themes threading through this year’s programme has been gender-based violence and the patriarchal attitudes that nurture it. In February 2022, SAPS statistics show that more than 900 women in South Africa were killed in just three months. Fringe productions from I am sorry, Whistleblowers, and River of Tears, to works on the curated programme, such as French performance artist Clare Delorme’s Clara Delorme: Double Bill, all addressed the lived experiences of women. In doing so, they are expanding liberty for all of us, even as the United States repeals Roe vs Wade. Clearly, the war against the patriarchy is long, but each step forward is ground gained, even if it is later lost.

Related to the push against patriarchy, queer identities and realities were also unpacked and explored in creative ways. With most of the festival falling over Pride Month, artists used this platform to challenge a society still catering to the heteronormative and cis-gendered. A stand out was 12 Labours, the interdisciplinary project by Standard Bank Young Artist Gavin Krastin, who rebels against the gender norms of performance. Two Fags and a Dancer, Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come in, and POP were amongst the most talked-about productions at Fest.

Identity was also a theme trickling through much of the programme. “Do South Africans have one distinctiveness connecting us as a nation?”, “If Ubuntu exists, how is it manifested today?” and “How are the differing experiences of race, inequalities, and privilege explored in the born-free generation?” are all questions stirred by several productions, amongst them were shows such as Is Everything Connected?, May I have this dance, and crowd-pleaser, Moya. The question of identity was even evident at the National Jazz Festival. Former Standard Bank Young Artist Benjamin Jephta used his compositions to present and further explore the importance of coloured identity.

Where there is art, there is politics, well, in South Africa at least, and for that, we can be grateful. Scathing critique of the state was evident in many productions as people grow ever more gatvol with corruption. Having to negotiate ANC footprints just to get a show, then praying it is not affected by load shedding, rubs salt into the raw wound. The Ward Councilor was a work based on actual events involving greed, power-hunger, and violence, all scenarios synonymous with corruption. This year marks a decade since the Marikana Massacre. As a response, the exhibition, Marikana 10 Years On, aimed to highlight the long-lasting emotional, economic, and psychological effects on family members of the deceased. Kak took no prisoners when it came to an eviscerating critique of government corruption and ineptitude.

As the first festival since the beginning of the pandemic, it is only expected that there was a collective post-covid feeling of liberation as a subtext. Whether referenced in scripts or made light of at The Very Big Comedy Show, the coronavirus was an infamous guest at this year’s Fest and will most likely be for years to come.

Over the last ten days, we have seen artists grappling with these and other topics. Politics, in one form or another, was dominant across the programme, reminiscent of artists’ responses to racialised state oppression in the ‘80s. And whether works were loved, revered, or dismissed by audiences and the (very few) critics, they stimulated conversation, brought us together, and changed all of us in various ways.

Bravo!