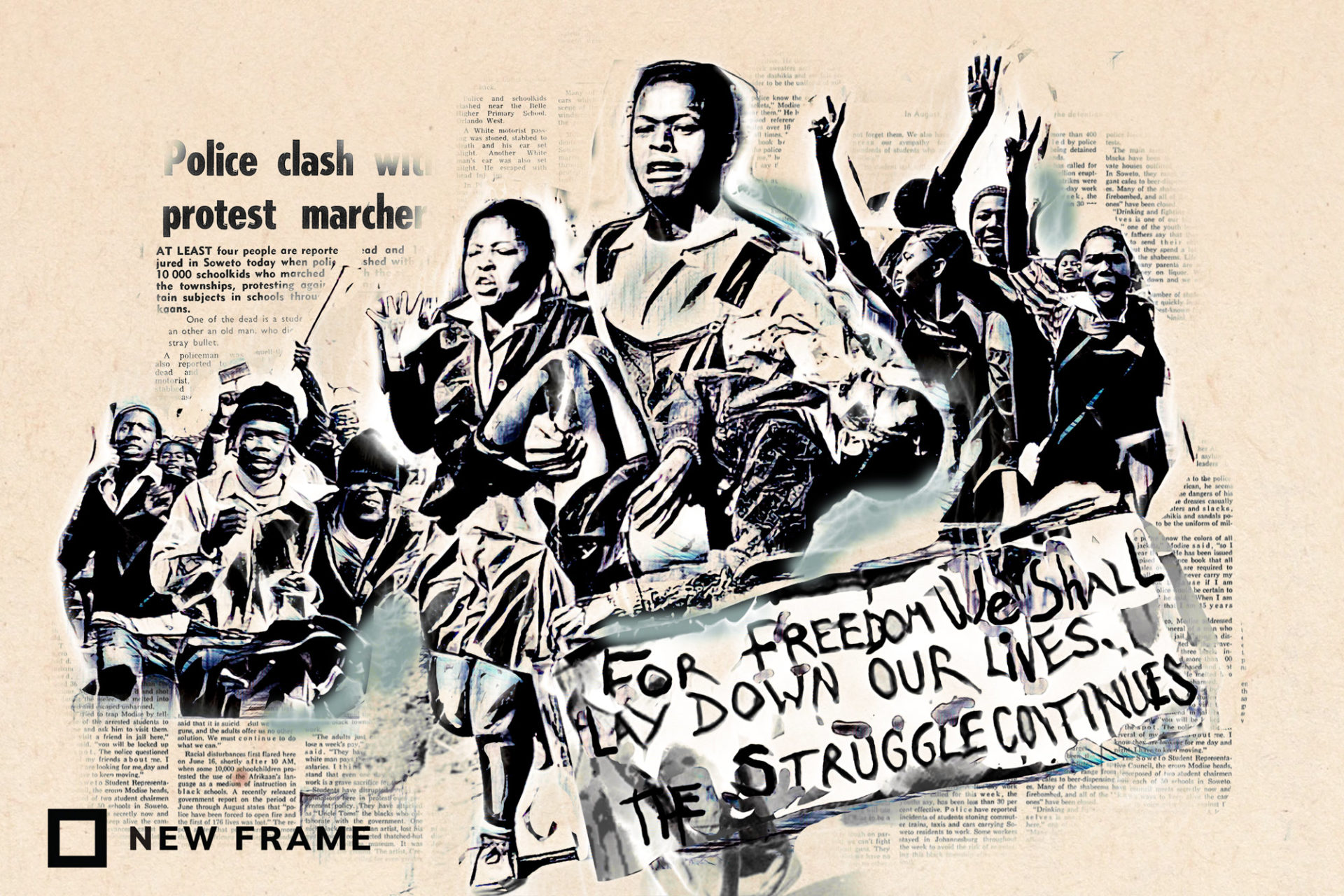

The class of 1976 shook off the previous generation’s climate of fear and showed the country what it could achieve through mobilisation. Now, more than ever, we need to take heed, write ENVER MOTALA and SALIM VALLY for New Frame.

The fact of the matter is that the rifles and ammunition that laid low Hector Pieterson and his comrades and sent the Tsietsi Mashininis into exile and the Dan Montsitsis into prison put an end to all illusions about achieving equality of conditions and of educational content as long as the system of racial capitalism [remained]in South Africa.

Neville Alexander, The Resonance of 1976

What is the real significance of 16 June 1976? Despite the annual commemoration of this momentous day, the context and origins of 16 June recede into the past. In recent years, this watershed event has been viewed primarily and simplistically as an event to celebrate the resistance to the forcible imposition of Afrikaans as a language of instruction on working-class schools in Black townships.

This was undoubtedly one of the factors that led to the events of 16 June 1976, but we need a deeper understanding of these events and their underlying causes.

Two overall issues relating to the apartheid or racial capitalist state are critical for understanding the events that took place in 1976.

The first has to do with the political economy of the apartheid state, the draconian political and economic system established in the interests of a racist minority in our country. The foundations of this racial capitalist system followed the conquest of the land and the development of a mining and industrial/farming capitalist system from as early as the 1700s, intensified from the 19th century onwards to lead eventually to the hateful apartheid regime in the middle of the 20th century.

The decision by high school students inspired by the Black Consciousness movement to protest on 16 June in Soweto – which quickly spread throughout South Africa/Azania – is inseparable from the political and economic conditions that faced impoverished and working-class communities. These conditions persist. It is a deeply entrenched system of exploitation in which poor wages and inadequate living conditions characterise the lives of the great majority. It reproduces poverty, increases unemployment – especially among young people – and the worst possible working conditions for those who can get jobs. It continues to perpetuate, despite important reforms, an unequal education system that reproduces inequality.

This system of racial capitalism, both before and after 1994, has led to material deprivation, food insecurity, and poor health and living conditions. After 1994, we removed the scaffolding of apartheid laws, but the building of inequality remains on firm foundations. Racial capitalism has resulted in the most monumental inequality, which, by some calculations, is the worst in the world. In other words, while the country has the resources to produce an extremely rich small group and a brazenly corrupt political elite, it simultaneously produces massive and unconscionable inequality and all its consequences for society. This is happening in a country with enough physical, environmental, material and intellectual resources to build a caring and compassionate nation.

The class of 1976 and the students of the mid-1980s demanded education for liberation. This education equality was inseparable from their vision of a fair and egalitarian society.

Self-sacrificing struggle

The second major cause of the events of 1976 was the draconian legal system of the apartheid state, which permitted no democratic or other forms of opposition. It was racist to its core and reproduced sexism in every avenue of life for all the people of South Africa. All forms of democratic organisation, protest and resistance were barred. Political, student, worker and community leaders were persecuted and murdered. Radical resistance was gunned down. Under those conditions, it was challenging and dangerous to organise resistance to the regime, especially because both the apartheid government and the capitalists were almost entirely at one about clamping down on resistance by political organisations, students, workers and communities.

The students that fought the apartheid state – soon after workers did the same in the 1973 strikes – ushered in a wave of unprecedented, courageous and self-sacrificing struggle to topple the racist regime and the exploitative economic system that it supported. They showed us that such a system was not invincible and that it could be challenged. They showed us that you could organise and mobilise secretly and publicly to challenge the system. They showed us that the armoured vehicles of the apartheid government were not unbreakable fortresses. And they showed us that the idea that the racist state was all-powerful was a myth and that millions of young people could be motivated to enter the resistance movement against it.

They showed, too, that it was possible to do these things in a non-sectarian way – that you did not have to belong to a particular political party to fight the state – and that a wide range of political, social, cultural, religious and social views could come together to fight for a common cause. They showed especially young schoolgoers that they too could join the fight and that it was not just limited to Soweto, as some accounts of 16 June seem to suggest. And they laid the basis for a much broader challenge against the apartheid state, reaching greater heights in the 1980s with workers and community organisations. Many political organisations, including the Azanian People’s Organisation, the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, the Unity Movement, the South African Communist Party and the ANC, as well as smaller and more recent organisations, were able to mobilise their membership because of the openings provided by the students and other social movements of the time. Much broader social movements and trade unions were born as a result, especially in the 1980s, to challenge the racial capitalist state.

The students of 1976 got rid of the climate of fear to which older generations had succumbed because of the persecutions of the 1960s. They gave rise to creative and radical intellectuals and organisers, marking a fundamental turning point in our history. The cult of personality was frowned upon, individualism and greed discouraged, and the collective and community encouraged. And through this, they also laid down a challenge for what we were meant to teach and to learn and how that was to be done, for what and whose purposes and towards what kind of social system.

Ending desperate times

June 1976 and the years that followed are enormously important not only in the country’s history but also for its relevance today. It should never be frozen in time because many of the issues facing the students and communities they come from continue to plague this country, although the first democratic elections took place in 1994.

It was hardly surprising that these same conditions motivated the students of 2015 to take to the streets demanding free quality higher education for all. We need hardly spell out the conditions that continue to face the vast majority of the people of South Africa so many years after 1994.

Who can say that the country is not in the grip of an unprecedented crisis given the levels of corruption, inequality, unemployment, poverty, food insecurity, poor education, crime, degrading health, mounting energy and transport costs, and levels of debt that the vast majority of the people must endure daily through no fault of their own? Even the middle classes in society are not spared these impoverishing effects. Who can argue that the power of narrow elitist and corporate interests does not rule the day now? Who can deny that we are witnessing the worst environmental problems that have given rise to the catastrophes we continue to see, with water shortages, floods, food deprivation and even children dying of starvation? Who can deny the utter desperation that gives rise to all the psychosocial trauma, gender-based and other forms of violence, xenophobia and social dysfunction we see daily?

The students showed through their courageous acts of self-sacrifice and their determination that no society needs to tolerate injustice or believe that nothing can be done to end these desperate times. They demonstrated to us what was possible through public mobilisation, education and democratic organisation. And they showed through them that such forms of mobilisation and organisation should not be limited to students alone since all of society is implicated in building a decent and humane social system by getting rid of the barriers that stand in the way of such a society.

Despite the despair in many communities and the cynicism of state officials, there is hope. It resides in the many students, educators and communities throughout our country fighting for an education system and a country befitting the sacrifices made by the hundreds of students killed in 1976. They are the ones who continue the legacy of the class of 1976.

Enver Motala and Salim Vally are currently guest-editing a special edition of the journal Education as Change on critical issues and alternatives in post-school education and training in South Africa.

This article first appeared in New Frame.