By CASEY LUDICK

In April 2017, my mother put me on an implanted form of birth control called the Implanon.

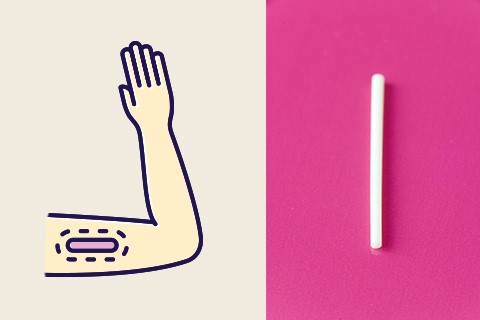

The Implanon is a flexible plastic rod, about the size of a toothpick, that slowly releases progestin, preventing ovulation. I had it from 2017 until about mid-August 2021. The maximum amount of usable time is three years anyways. By mid-2020, my skin was an acne-ridden mess, and I had gained a bunch of weight, as many women on birth control do.

I was also getting a period almost every two weeks. The Implanon was releasing less progestin near the end of its cycle, which caused minor issues like those mentioned above. The longer the device remains, the less effective it becomes, so leaving it past the maximum point puts the host at risk of pregnancy.

Unsure about where to go, and despite the risk, I bumbled about building up the courage to deal with my birth control. At the end of June, I finally decided to have my Implanon removed in Makhanda through the university’s Health Care Centre (HCC). The nurses and I were seriously unprepared for the amount of time I would spend at the HCC over the next week or so. With Covid-19 taking precedence in the health care industry, more women were struggling to access birth control – a small issue, perhaps, compared with the pandemic. No, but really, there were so many things I could have been doing instead of trying to have my Implanon removed. Schoolwork, for example.

I went to the clinic on Thursday, 5 August. I took my book and cellphone and made the trek through campus up to the small offices. Upon arrival, I was told that the nurse who was qualified to perform the removal procedure worked at the HCC part-time due to Covid. I was told to return the following Tuesday, 10 August, when she was expected at the clinic. The weekend passes, and Tuesday comes, so I walk back up the hill at 8 am

I was told to book an appointment for later in the day. I confirmed that appointment with the Health Care Centre via email and returned at the stipulated time but was turned away again.

This time, the nurse I needed to see had come in contact with someone who tested positive for Covid-19. As per protocol, she went into isolation for fourteen days. So, I was discretely pulled into a unit, where a nurse referred me to the women’s hospital at Settlers Hospital. At this point, I had already surpassed the daily 10 000 steps required for a long and healthy life, and I was exhausted. But nothing could be done, so I walked home with my Implanon still stuck in my arm.

The following day, I got as far as the front desk, where the receptionist informed me that the hospital doesn’t perform removals before redirecting me to the Town Clinic. She assured me that they did removals. At the Town Clinic (Anglo African Clinic Dispensary), the receptionists informed me that the nurses only inserted the Implanon and that removal wasn’t available there. They then pointed me in the direction of Settlers Day Hospital. I went home.

On Friday morning, I picked up where I left off, as organised by the nurse at the HCC. I was more than ready to have this hormonal matchstick removed and be done with this situation altogether. That isn’t what happened at all.

The procedure usually starts with an incision near the bottom of the Implanon, then pressing down on the top end, which forces the bottom end out of the hole – like removing a splinter. My procedure, however, was much more complicated. So first, she measured the Implanon to check where she needed to make the incision. Then she injected me with a local anaesthetic and began to cut. She cut through more flesh than I had expected, and it was jarring, but I wasn’t super surprised. She then began to forcefully remove the hormone matchstick from its rental home. After struggling for some time, she called in another nurse to hold the forceps.

She was trying to pull the device from the bloodied cut. Eventually, she decided to take a break, so she cleaned up the wound and sent me back to the waiting room. Only to call me back again, so she could try another method. This was a cycle for that first visit. She would clean me up and send me out, only to call me back inside to try again. Essentially the same thing she tried before, just harder. I was in pain for two reasons. One, there was a hole in my arm and two, chaffing. She injected more numbing anaesthetic and then made a second incision, hoping it would be closer to the end of the Implanon. She pushed harder, but nothing really happened.

Amid numbing, chafing and cutting, both nurses asked me why I had gained so much weight. What was I eating, did I exercise regularly, why was I clearly so much bigger than when this device was inserted – when I was 17. Of course, I thought it was strange that they were commenting on my weight, and I was hurt, but one of them had a blade to my arm just minutes prior, so what was I going to do.

I left the clinic that day weak, hurt and in tears.

I returned to the day hospital again Friday morning the following week, this time with a witness. I saw an entirely different nurse this time who was able to remove my Implanon. She made the third incision (the others had healed), squeezed gently and then said, “I mustn’t panic” when it didn’t move. Taking deep breaths, she brought out a pair of forceps, stuck it in the numbed wound and then pulled it out by its middle.

One end flops up and then down. Then she just pulled it out. It was a weird note to end on because it took so much time and energy, but it was such a simple procedure. I watched the tiny, bloodstained rod be pulled from my arm, and I almost wanted to ask if I could keep it.