By JOY HINYIKIWILE

Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) was implemented in SA schools in 2000 as part of Life Orientation to contribute positively to adolescent sexual health in a holistic manner.

But is it succeeding?

Catriona Macleod, a Rhodes University psychology professor and SARChl Chair in Critical Studies in Sexuality and Reproduction, recently delivered a lecture to the Friends of the Library titled, ‘How school-based sexuality education fails South African youth’.

Macleod said many young people receive lessons on sexuality in schools, which is still the best way to reach most of the country’s youth. But, she pointed to four problematic themes in the sexuality education curriculum.

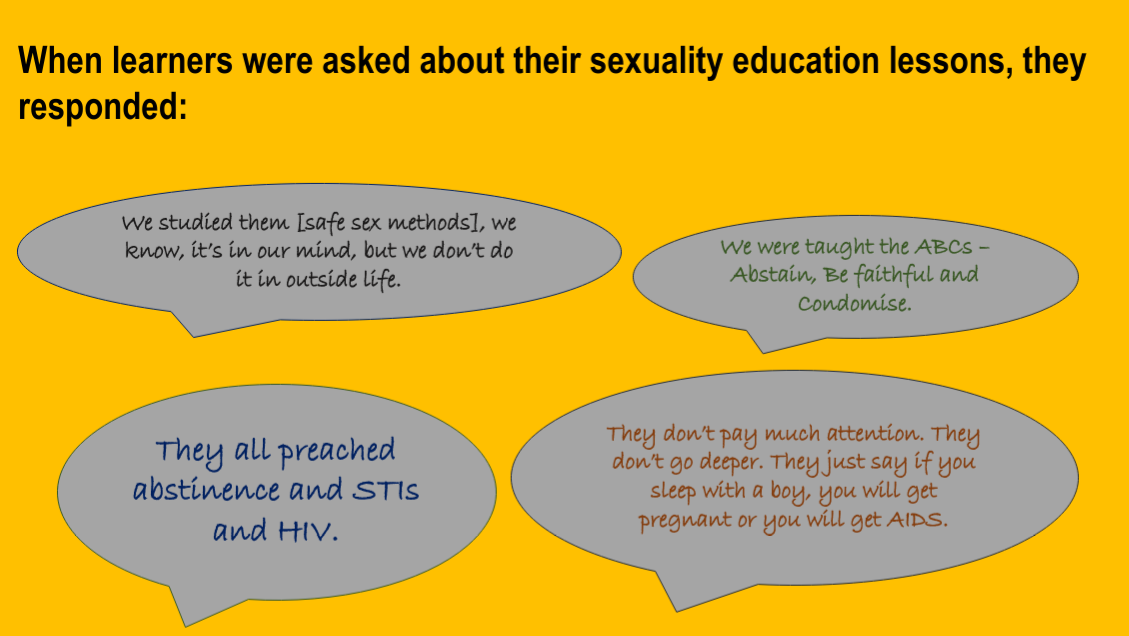

1. Disconnection

There is an apparent disconnect between what children learn at school and what they practise outside.

Macleod said learners found the content did not echo the complexities of their lives. It was “irrelevant” and “disconnected”. The curriculum is heavily focused on abstinence – the ideal learner is presented as a-sexual or alternatively ‘innocent’. The teaching style is teacher-centred and not relational. Messages do not connect with experiences of what learners want to be doing in the world.

Learners are looking for stories and clear examples. They want to ask questions.

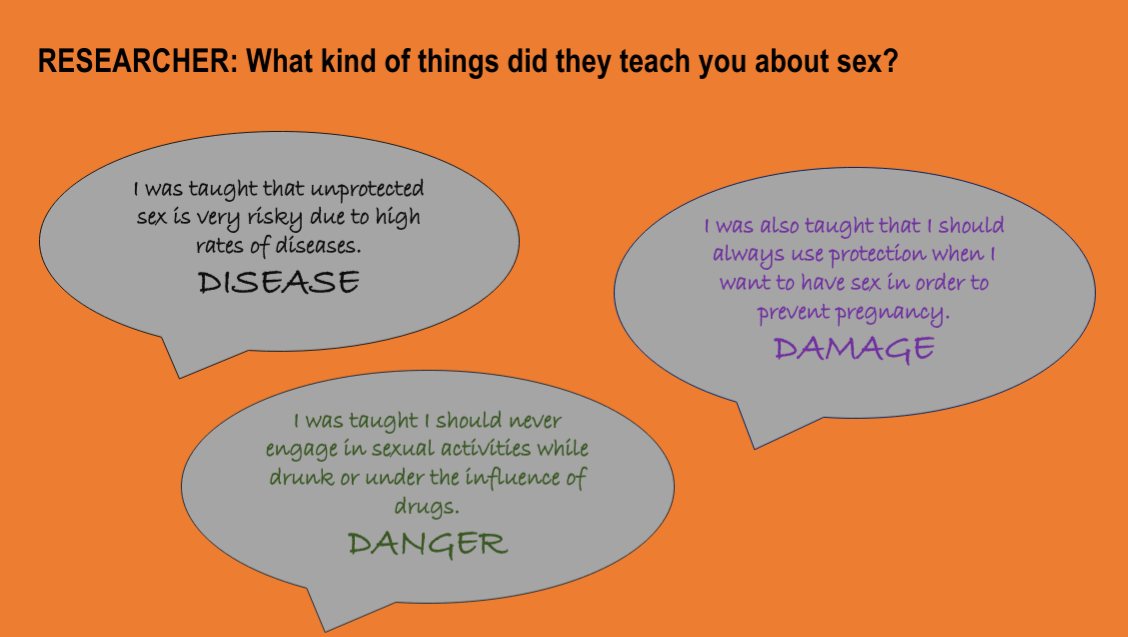

2. Sexuality education emphasises danger, disease and damage

“The fundamental premise of a lot of sexuality education is risk talk,” MacLeod said. Learners are taught that sexual engagement carries a risk of getting a disease. The damage discourse centres on the idea that your life is damaged if you get pregnant as a young woman. There is also the danger of being exposed to sexual violence.

“The message is, ‘Don’t get pregnant, don’t get a disease, don’t have sex, don’t destroy your life’. It’s negative messaging.”

The curriculum is also often taught through a series of moral injunctions. The billboard below by the Department of Health exemplifies the kind of messages and priorities that are impressed on learners.

MacLeod said the messaging is often directed exclusively at girls. It places the responsibility on girls for any occurrence of coercive sex, transactional sex and sexual violence. It puts pressure on girls and individuals to prevent the risks and dangers of sexual engagements rather than addressing any social and gendered dynamics that lead to this.

For example, in transactional sex, where women and girls engage in sexual activities with primarily men older than themselves in exchange for gifts and money, the curriculum does not consider that for many young women, transactional sex is for survival.

This often occurs in disadvantaged communities where women use transactional sex to feed their families. The lessons only serve to make girls take the blame and feel guilty. “It positions them as the bad person as opposed to the system in which their source of income is through transactional sex.”

3. Rigid Gender Norms

- The curriculum usually contains heteronormative tropes of how women and men should interact in intimate partnerships. Men are described as dominant. Their desires and needs are foregrounded, and the belief that men biologically have a sexual drive that needs to be fulfilled is maintained. Women are seen as submissive and vulnerable but are held responsible for maintaining the boundaries of decency in relationships regardless of the social situation.

- Rigid gendered hierarchies are also maintained even in biological talks. There is no discussion about intersex bodies and the variability of sexual organs.

- The curriculum fails to undermine the fundamental premise of sexual violence, which is often rooted in sexual inequity.

- It is silent on LGBTQI+ issues; when they are mentioned, they are ghettoised. They are mentioned in a secluded section and hardly discussed again.

- Heterosexuality is preached as a norm, and the prevalent homophobia in schools is not addressed

4. How easy is it for teachers to teach sexuality education

MacLeod said teaching sexuality education requires open dialogue. But for many South African schools, crowded classrooms make it difficult for teachers to hold dialogues and discussions. Both learners and school management are apathetic about Life Orientation as a subject. As a result, the subject tends to be assigned to teachers regardless of their qualifications or aptitude.

The lack of moderation may also create a school culture that is not conducive to productive sexuality education. Teachers may also find it hard to navigate the school culture and local cultural issues around sexuality education.

Lastly, a lot is expected from LO teachers, who should ideally also fulfil roles such as confidants and counsellors for learners. This may make it challenging to teach sexuality education effectively.

Implications and recommendations

MacLeod recommends the following changes to ensure effective sexuality education:

- Move away from teaching and telling and focus on dialogue, communication and listening. Allow learners to ask questions, whether directly or indirectly.

- Provide safe spaces for in-depth and honest conversation.

- Be aware of the way youth approach sexuality. Consider the music they listen to and the informal language they use to talk about sex.

- Scare tactics don’t help.

- Balance positive aspects of sex along with potential risks.

- Challenge gendered norms.

- Highlight the fluidity of gender categories and sexuality and have that embedded throughout lessons.

- Acknowledge teachers’ difficulties in teaching sexuality education, and provide support and workshops.

MacLeod said the stakes of sexuality education in South Africa are high. Our high levels of HIV, sexual cohesion and violence, unplanned pregnancies amongst young people, mortal maternity, hate crime, unsafe abortion, etc., place a great need for effective sexuality education.

She referred to it as sexuality education rather than sex education because sexuality is a broader term that describes all matters related to sexual experiences.