There are three amazing things about this wonderful account of the Moon landing 50 years ago. The first is the event itself, of course. But then there’s the fact that this world-changing event was experienced by a family huddled around a crackling transistor radio. And then there’s the wonderful shoebox that Steven Lang has kept the clippings in for 50 years.

There are three amazing things about this wonderful account of the Moon landing 50 years ago. The first is the event itself, of course. But then there’s the fact that this world-changing event was experienced by a family huddled around a crackling transistor radio. And then there’s the wonderful shoebox that Steven Lang has kept the clippings in for 50 years.

Almost too anxious to breathe, my family huddled around the transistor radio as every few seconds a high pitched beep punctuated the muffled speech that held an entire planet in awe. American astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin guided the landing module on towards its final destination – the surface of the moon.

My Father and I quietly looked at one another, not sure we could believe what we were witnessing. My Mother and sister sat silently as we listened attentively to the radio broadcast. Our family had discussed the space flights often in the previous months. We had followed the earlier missions, Apollo 8 and Apollo 10 as they went into lunar orbits. It was the most spectacular time in the most ambitious space programme ever.

As the lunar lander made its final approach, it was a moment of joy and a vicarious sense of achievement in sharing the most amazing discovery with my family, with the astronauts, and with the whole world. We were tense but we never doubted that the mission would succeed even though Houston had just reported only 30 seconds of fuel remaining.

The landing might be bumpy and they might set the lander down at an uncomfortable angle – but they were there, just a few feet above the lunar surface.

I was almost fifteen when we heard Armstrong make the most understated declaration of all time: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Today, fifty years after the first men walked on the moon, the magnitude of the triumph has not been surpassed.

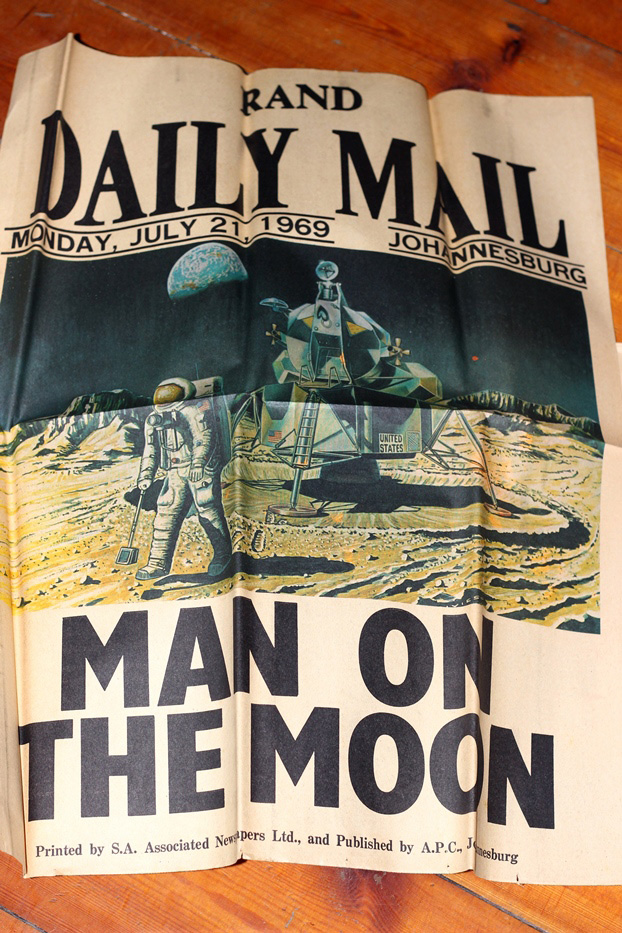

There was only one headline in every newspaper in the world, only one event that all the radios were talking about and only one set of images the TV stations of the world were showing. Sadly, we did not have television in South Africa. The then Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, Dr Albert Herzog, said this country would only have TV over his dead body.

A few days after the two Americans had walked on the moon, Wits University showed tapes of the event at the Johannesburg Planetarium. The grainy, black-and-white images were shown on several TV sets placed inside the dome of the planetarium.

I went with my school-mates so that we could see for ourselves what it looked like to be on the moon. We watched the series over and over. It was the first time I had seen a TV set and it was the first time I had seen men walk on the lunar surface.

It was incredible, but somehow, not quite as extraordinary, as it had been listening to the “live” radio broadcast of the landing. The barely audible sounds coupled with my imagination made for much better pictures than the fuzzy TV images.

It is hard for people today to appreciate the extent that the Apollo programme transfixed the world. Reports say that over 500 million people watched the landing on TV, but no one is able to hazard a guess as to how many people listened to it on radio – like my family did.