BRAD & BUTTER

INTENT

Bradley Manaka is a free-lance community journalist located in Makhanda, Eastern Cape. Brad uses photography, writing, audio and video to document the livelihoods and everyday efforts of ordinary citizens to put food on the table in the dysfunctional Makana Municipality.

The Collection

My capstone project is a collection of work based on solutions journalism learnt in the Postgraduate Diploma in Journalism and Media Studies (PGDIP) course at Rhodes University. My portfolio building-capstone project documents the state of business in Makhanda. I focus on the impact of government malfeasance and the Covid-19 pandemic National State of Disaster on entrepreneurs and explore solutions to the challenges they encounter.

My capstone project is inspired by half a decade of Makhanda residency and dissatisfaction with the poor service delivery and economic inequality.

I integrate teachings from my PGDIP course that introduce different approaches to research and journalism, narratives from individual perspectives, and the various ways they intersect to push back or reproduce social ills.

I adopt a people-centred approach to reporting and aim to identify community concerns, the cause, and mechanisms that can be used to address them.

Further developing from my documentation of Makhanda’s rural economy of donkey cart owners, I highlight efforts to connect informal businesses to Makana Municipality’s economic development programmes. I also explore opportunities to document various businesses in Makhanda and expose them to audiences within and outside the business sector.

The capstone project is enriched by community journalism from my internship at Grocott’s Mail and primarily uses writing and photography as modes of media.

Soap Building Blocks

Andiswa Stofu, 30, is a self-taught creative and entrepreneur from Extension 9 in Makhanda.

In 2015 Andiswa was invited by Rhodes University’s Enactus student society – a global non-profit and community of student, academic, and business leaders promoting socio-entrepreneurship- to start her own soap business Enhanced Aloes.

“Enactus had a promo competition. I looked on YouTube and everything, and I went with it.”

Andiswa watched YouTube tutorials to learn how soap is made and began experimenting with making her soap. She uses several products, including essential oils like coconut oil and clay, to produce her soap blend. A chemistry expert assisted her at Rhodes’ Pharmacy Department to ensure that her soap was suitable for human use.

Although Andiswa is a part-time domestic worker, she puts great attention in ensuring that her products attract customers’ eyes at local markets.

She has expanded her business into making shower gels and jewellery using beads and artistically using everyday items such as keys.

When asked about what she attributes to her creativity, Andiswa says she was born creative.

“It was given to me by the grace of God. I have always been creative.”

She was introduced to shweshwe, a printed and dyed cotton fabric, in 2019 and used it to create book covers and dresses.

She has a supplier located in Pretoria with an online store where she orders the raw soap in bulk to cut costs.

“Fifty milliliters of soap is R110 here, but from her, it’s R40 or R60. It takes R70 to courier it here, so everything is cheaper.”

Andiswa says her soaps sell like hotcakes.

“Everybody needs a counter book. The wives want it for a shopping list, and the husband wants to write their tools in there. My dad has one to keep a record of his goats, when they were born, and all the details.”

She initially used plastic to package her soaps but switched to brown wrapping paper to prevent melting due to heat.

She refers to her marketing style as “ambush selling” whereby she approaches people mainly in markets in Makhanda West and introduces them to her products.

“My customers like that it’s organic, and the price is not so bad.”

Andiswa relies on local markets such as the Albany Market club to sell her products. She would like to expand to markets in Bathurst but says the travel expenses are too costly.

Andiswa’s business is registered as a proprietary company (PTY) at the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) and listed at the Makana Municipality Local Economic Development (LED) database. She has, however, not been contacted by the LED office for opportunities to grow her business.

The Covid-19 National State of Disaster regulations did not spare her business as she could not sell her products. Some of her soap melted, and she was forced to give them away for free to residents in her community.

“It hit me bad. It gave me time to do most of the stuff but financially, it was straining. It was a very dark place. I wouldn’t go back there. At least the markets are starting to pick up again.”

Enhanced Aloes currently has a Facebook page but Andiswa aims to expand her online presence to other social media platforms and a live website. She has high hopes for her business exploits and, as a youth herself, believes more needs to be done to curb the youth unemployment plaguing Makhanda.

“My long-term goal is to have a business located at Joza Mall and would like to employ 50 youths. If you’re young and creative and want a place to showcase your ability, you should be able to come. I want businesses from town to come here and collect items for shelves at their stores.”, she said.

Fruitful Talk

In September this year, I published a story in Grocott’s Mail informing readers about the Department of Economic Development, Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEDEAT) grants to sustain and propel local small businesses.

Remaining committed to the development of Makhanda’s economy, I interviewed local store owners and street vendors that sell fruits and vegetables to find out about the operations of their businesses under the Covid-19 National State of Disaster.

Fresh fruits & veggies win the streets

Weston Geza, 45, sells fruits and vegetables on Beaufort Street beside the SAPS station. He started his business six years ago and currently employs four workers.

Starting a business was not in Geza’s initial plans, but he decided to do so after unsuccessful attempts at finding employment.

“After having looked for a long time for work, I decided to start for myself.”

Geza sources his fruits and vegetables from various suppliers in Makhanda, including Radway Green Farm, Yarrow Farm, Committees Drift.

“There are a lot of our own farmers, African farmers who were given land by the government. They are specialising mainly on beetroot, cauliflower, spinach and cabbage.”

Geza also gets oranges from suppliers at Fort Beaufort and Adelaide.

Geza sites that it took a while for his business to take off, and his supply of fruits and vegetables would rot. As time progressed, however, Geza became known in the area and developed trust from customers.

Although Geza was hit hard by Level 5 Covid-19 Regulations of March 2020, he did not seek assistance from the government to sustain his business. Instead, he opted to wait for the relaxation of the regulations and attain a trading permit at Makana Municipality.

“I’ve heard about those opportunities but myself being a foreign national, although legally in the country, I thought to myself it would be a long process to start looking for money and all the help I can get from government. so I just forgot about those things and just soldiered on.”

Although informal businesses were allowed to operate earlier than most other sectors, Geza says there was a decline in sales as there were fewer customers due to people not having money.

Weston highlights that he managed to attract diverse customers: “Here we serve everyone – black, white, Coloured…Black people from the location and than some white people because our food is fresh.”

Unlike popular stores in Makhanda, his fruits and vegetables are not preserved by fridges. They are therefore sourced and limited to be sold daily to prevent having excess produce that goes foul.

“I think the government should create more employment and find ways for people to work even under such difficult circumstances.”

Informal traders request assistance

Nothando Qude is a mother of five children and has run her fruits and vegetable business on Beaufort Street for 30 years.

She buys her supplies from foreign-owned stores in the area. Qude laments that the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on the economy have resulted in fewer customers.

“There’s no business; people don’t have money as they’re unemployed. We’re suffering. You can sit the whole afternoon without selling anything.”

Qude says she has attended multiple meetings at City Hall but could not get assistance to uplift her business. At the time of the interview, she was unaware of the government grants for informal businesses of up to R30 000 to sustain and propel their businesses revealed by the Department of Economic Development, Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEDEAT) at an information session for informal business in September.

“I didn’t know about the meeting at town hall. We need someone who will speak for us. Some people say they stand for us, but we hardly see them.”

Qude wishes for more effective communication when business programmes get introduced. She continues to rely on customers travelling in and out of Makhanda.

“I’ve been helped by people who buy my food so that I can also go to Shoprite and buy food. So that we can eat at home.”

Grahamstown Fruit & Veg going strong

Dianna Chibvongodze, 35, is the manager at Grahamstown Fruit and Veg, located at Bathurst Street in the Makhanda CBD.

She and her partner started the fruits and vegetable business in a passage at a store that sells second-hand furniture and in 2017 relocated to Bathurst Street to expand their business.

Grahamstown Fruit and Veg has seen significant growth and currently boasts 14 employees. Chibvongodze, however, says the development of the business has produced new challenges of delivery demands.

“You know when you’re starting something, you need more labour than you need more transport for delivering.”

Grahamstown Fruit and Veg did not get spared from a decline in sales due to the national state of disaster’s Covid-19 regulations last year.

Chibvongodze says the store survived without any assistance.

Chibvongodze says popular items at the store include potatoes, onions, and cauliflower.

“I would recommend them to come here because we will help if they want to build their businesses because we have wholesale prices.”

Solutions Journalism for Makhanda

Journalism continuously evolves. The profession has risen into storytelling with specific approaches. Solutions journalism, the method I have adopted in the last year, is one such branch of journalism. Solutions journalism involves storytelling that brings new information to the public, identifying challenges, and exploring opportunities to reconcile the parties in question.

Following my documentation of donkey cart business owners earlier this year, I aimed to resolve some of the donkey cart owners’ hindrances to business operations. The donkey cart owners raised several issues, including difficulties accessing healthcare for their donkeys, shabby donkey cart building materials, and an inability to access private land for wood used for fire and building mud houses.

Access to land has proven to be our country’s perennial bone of contention. A new bill proposal to amend Section 25 of the Constitution to allow land expropriation without compensation to speed up land reform processes is yet to be legislated by parliament. The bill’s targeted beneficiaries, such as donkey cart business operators, will have to wait a bit longer.

I, however, sought a remedy to concerns that can be addressed timeously. I have connected donkey cart owners in need of medical attention for their donkeys to the local non-profit Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). I requested assistance on behalf of donkey cart owners in Zolani by messaging the organisation on its Facebook page. My actions resulted in a joint effort with SPCA Grahamstown to map and compile a list of donkey cart owners in Makhanda.

“We are hoping to form a donkey owners’ group. The idea is to get the owners’ details and their carts and donkeys on a database. We would then have donkey days from time to time and try to give responsible owners vet assistance, help with harnesses, and maybe groceries if we can get sponsored. The idea is that those part of the group must have a number displayed on their carts so that the public can report any whipping etc. We will know who it is, and they will not benefit at our donkey day.”, said SPCA Grahamstown.

I have compiled the contact details and addresses of at least six donkey cart owners to assist the SPCA’s efforts to better the lives of donkey cart owners and their donkeys. The compilation is ongoing, and I remain in touch with the donkey cart owners to share information about the latest opportunities available to sustain their businesses.

In September this year, as an intern at Grocott’s Mail, I published a story informing readers about the Department of Economic Development, Environmental Affairs, and Tourism (DEDEAT) grants to sustain and propel local small businesses.

The Eastern Cape Provincial Informal Business Policy Framework responds to Makhanda’s proliferation of unlicensed informal businesses and incentivise traders to attain permits. This will enable informal traders to access grants of up to R30 000 to sustain and propel their businesses.

A roadshow was promised to educate and assist informal traders on the minimum requirements of access to funding, including being run full-time by the owner with a valid SA identity document, how to fill in the application forms, in operation for a minimum of six months, and with a valid proof of residence in Makana Municipality.

However, several interviews with informal traders suggested that efforts to make communities aware of the opportunity were lackluster, and numerous informal traders, including cobblers, donkey cart owners, hairs stylists, and fruit and vegetable street vendors, were unaware of the funding opportunity.

I was compelled to speedily publish information about informal business funding on Grocott’s Mail. I had confidence that it would have a broader reach than Brad and Butter due to its locality in Makhanda. I also fetched the application forms at the Makana Municipality LED office. I foot soldiered across Makhanda East, including Vergenoeg, Phola Park, and Vukani to deliver them to the informal traders.

I found it consistent among the business owners that the Covid-19 regulations have had a detrimental effect on them, most unable to operate during the hard lockdown of March 2020. Most business owners indicated that they had to fend for themselves by using private funds or relying on their few clients for an income. There seemed to be a lack of trust in the government funding processes, and some business owners were reluctant to apply for SMME Covid-19 TERS funds or funds allocated to the informal sector.

The question of why business owners sometimes display a reluctance to apply for the opportunities is the perceived complexity and lack of trust in the application processes. There’s an urgent need for simplification and education on applying for the government programmes for the businesses to be willing to apply and attain funding to sustain their businesses and the Makhanda economy.

While a commitment to solving problems informs solutions journalism, it is essential to be wary of overcommitting to stories. I have to avoid taking on unmanageable requests from the subjects of my stories.

One example of an unmanageable request is from a cobbler I shared the informal business application forms with, who requested that I return to his stand on Beaufort Street the next day to take the filled forms to the Makana Municipality LED office on his behalf. The request was inconvenient for me and would not benefit the applicant as physical confirmation of his identity is required. It could also result in missing out on the opportunity to be guided by municipality officials on the way to apply correctly.

It is necessary to reaffirm my role as a journalist as a sharer of information to avoid misrepresentation into a substitute for public servants and active citizens in communities. The news circulated is geared at further advancing existing community efforts of active citizenship and journalists should not assume the function of mandated stakeholders such as citizens, businesses, or the government.

Business owners in both Makhanda East and West were receptive to interview requests to promote their businesses. Joza Assumption Development Centre (ADC), a skills training and small business development centre in Joza Township, programme coordinator Masonwabe Nduna invited me to profile small businesses in Makhanda East to link them to a client base in Makhanda West. Nduna’s vision coincided with my solutions journalism, enabling me to tell stories that recognise and develop economic activity in Makhanda. It will go a long way in creating an environment conducive to business and result in a decline in the current high unemployment rate that, according to Stats SA, sits at 32,5%.

I primarily reported on party election campaigns, conduct, and voter participation or the lack thereof. I familiarised myself with the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC) guidelines on media coverage on Election Day.

The South African National Editor’s Forum (SANEF) Election Training Webinars were offered free of charge upon registration by journalists from mainstream and community media in August and September this year. Viewing recordings of some of the seminars provided necessary awareness into centering the voter experience instead of reducing people into statistics.

Grocott’s Mail’s community-oriented approach to journalism provided the ideal platform for fair, balanced, and humane election coverage focusing closely on the reasons why people voted on the day that according to projections by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research marked South Africa’s worst voter turnout of 48%. I pose this question to try and understand from the pool of voters what they consider to be the solutions to poor service delivery.

My work leans on solutions journalism at Grocott’s Mail while maintaining one eye on my capstone project about the impact of government malfeasance and the Covid-19 pandemic National State of Disaster on entrepreneurs. I retain a storytelling thread that is consistently oriented towards economic activity from business owners, primarily in Makhanda East. What started as documenting the contribution of donkey cart owners to Makhanda’s economy has exposed diverse ways people earn an income in our town. I attempt to link the business owners to audiences and potential clients throughout Makhanda through promotional storytelling and programmes that help entrepreneurs flourish. My approach to journalism avoids leaving the subjects of my stories hanging and audiences falling victim to despair and nihilism. Ultimately, my work is about raising awareness about how the media can operate as a mechanism for development and a catalyst of active citizenship.

Freelancer at Your Service

As I further my studies at Rhodes University and remain an invested resident of Makhanda, I intend to stay an avid free-lance contributor at Grocott’s Mail.

I will lean on my strength as a writer to simplify information for the residents of our town so that they are well-informed about issues that impact their lives and those of others, participate in resolution processes and get hands-on in seeing them through.

I am cognisant of the need for resources and time to produce extensive research and public value journalism. I avail myself to progressive institutions and publications committed to advancing sustainable journalism.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Makhanda East Donkey cart owner Vuyiseni Yako, left, harnesses his two donkeys with the help of his teenage neighbour in white, friend in the centre and child on the left in preparation for his drive to a woodland near a local farm. Vuyiseni has two donkey carts and borrowed his friend one. On Saturday morning, 12 June 2021, Vuyiseni drives his small donkey cart from Zolani to his friend’s house in Joza to fetch his bigger cart because it is stronger and can carry a heavier load. Photo: Brad Manaka

The drive to the woodland takes off to a slow start after Vuyiseni identifies that the harnesses are not properly tied to the donkeys. His 10-year-old-son Asenathi and 15-year-old neighbour Phumlani climb off the cart to help him tie the harnesses. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni drives his donkey Cart on a trail on grazing land en route to the woodlands. Photo: Brad Manaka

The donkey cart arrives at the woodlands and the donkeys eat grass in the shade. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni identifies a dry natural trench with thick-branched trees that he knows and climbs down in search of fire wood. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni cuts long branches from trees with a bow saw. Photo: Brad Manaka

The two boys patiently watch as Vuyiseni cuts branches while balancing on a stem. The boys assist Vuyiseni with different cutting tools. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni’s neighbour carries a branch and walks away from the trench. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni puts the cut wood on the cart. The boys piled the wood near the cart for Vuyiseni to orderly pile them on the cart. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni ties a long strap into nots to ensure that the wood is securely tied on the cart. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni and the boys pull the donkeys out of the woodlands and onto the N2 highway. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni pulls the donkeys onto the left side of the road , slows them down and prepares to hop onto the cart. Asenathi sits on a cushion on top of the wood and eats sugary wild plant seeds picked on the side of the road. Photo: Brad Manaka

The donkeys gallop faster on a steep tarred road en route back to Zolani. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni and Phumlani arrive in the afternoon in their Zolani neighbourhood. Photo: Brad Manaka

Vuyiseni poses for a portrait at his home after parking his cart.

Photo: Brad Manaka

WRITING

Recognising Donkey Carts

South Africa’s rural economies are synonymous with the use of donkey carts. The long-standing mode of transport remains resourceful to the poor, subsistence farmers, and untarred communities. Makhanda’s location in the semi-urban Makana Municipality is similarly characterised. However, donkey cart owners share roads with other motorists – with some steering the latest and speediest vehicles. This has resulted in rising disregard from road rage inclined motorists that endanger the lives of donkey cart drivers and their donkeys.

Although animal-drawn vehicles have official recognition as road users under the Road Traffic Regulations of the Department of Transport, owners of the vehicles encounter disregard from motorists. This is exacerbated by animal-drawn vehicles prone to faults, breakdowns, and at risk of collisions. These are detrimental to animal-drawn vehicles’ resourcefulness to their owners and make marginalised communities further vulnerable to poverty.

The Department of Transport published a policy statement titled “An Animal Drawn Transportation Policy for South Africa” in 2007. The document recognised the value of animal-drawn vehicles to residents of rural South Africa for travel, selling goods, transporting water and wood. It aimed to remove barriers to the integration of animal-drawn vehicles into official roads and cities. It also aimed to maximise the social and economic benefits of linking rural parts to urban areas.

Makhanda East consists of townships where the use of donkey carts is common. The animal-drawn vehicles are a source of income to households through the collection, transportation, and sale of wood and provision of affordable moving services in Makhanda’s impoverished communities.

However, on Zolani’s Phumlani Street, households encounter challenges caring for their donkeys and maintenance of their donkey carts. Phumlani resident Ntombovuyo Guzi is a mother of three and unemployed. She lives with her partner Lungisani Ncapayi. She depends on her children’s social grants to feed her children and says that her partner uses his donkey cart to earn a living by collecting and selling wood and providing moving services: “He (Lungisani) doesn’t work. He only uses the donkeys. I also don’t work. I only make ends meet by doing laundry there (at a person). I can perhaps get R150 to buy something to eat.”

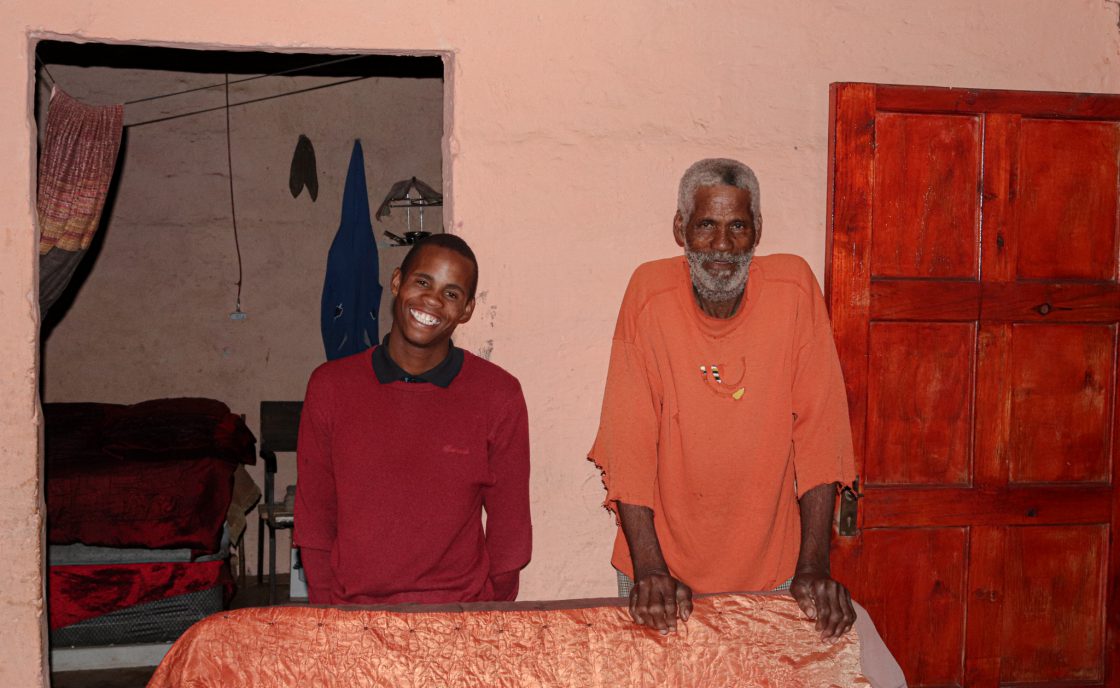

In another home on Zolani’s Phumlani Street, pensioner Dadora Madoda is a donkey cart owner. Madoda uses his donkey carts to transport wood that he collects at nearby bushes. The wood is sold to Makhanda East residents for fire and as building material for mud houses. Dadora lives in a home of five with only his son-in-law employed as a local contractor. Dadora also intends to use the wood he collects to build a two-room mud house for himself and his unemployed 18-year-old grandson Simma on a nearby plot of land and move out of the family home.

“If we don’t have donkey carts we won’t be able to build houses with rooms. My grandson is going to have his own house. He is going to move out, you understand, so he will have his own place with his girlfriend and not in this house”, says Madoda.

From providing economic mobility between Makhanda East and Makhanda West to transporting building material in a country with a perpetual social housing backlog, donkey cart owners remain the unsung heroes of rural South Africa. Broader attention to the work they do to motorists, the government, and the public will go a long way in addressing the challenges donkey cart owners encounter, maximise the opportunities they present, and ensure that they are treated as equal road users by all motorists.

Tata Omkhulu Ngwevu & His 60 Year Donkey Cart Business

A softly spoken listener Tata Omkhulu Ngwevu is content with his few words. A man used to slowing down and staying on his own route just as he does with his donkey cart, Tata Omkhulu has sustained himself and his family for 60 years with his donkeys.

The 75-year-old was born and raised in Tyanti in Makhanda East and was introduced to donkeys early on in his life by a man he shared a yard with who taught him the ins and outs of donkey rearing.

In 1961 Ngwevu found himself without work. He decided to start his own business and purchased donkeys – and he has not looked back. Ngwevu collects wood used for fire and as building material at a woodlands at Stone Hill and Water Springs and sells it to his community members. He also transported people’s possessions upon request.

Sitting on a sofa facing the door at his home in Vukani, Tata Omkhulu had been listening to the radio and patiently awaiting my arrival. Although he only speaks when spoken to and compels formality, his welcoming demeanor evokes calm.

The upright senior citizen expresses concern with the way young people mistreat and misuse donkeys. Ngwevu prides himself in treating his donkeys well by hydrating them with water and feeding them grass regularly, especially after trips, and getting in touch with the SPCA when they are unwell.

Ngwevu prides himself in the healthy state of his donkeys. He has received numerous requests from people to take pictures in Makhanda West including a newly wed couple in 2013.

He says that when he was a young adult males were usually the only people allowed to drive donkey carts but as time progressed children began to use donkey carts. He says this has negatively affected the wellbeing of donkeys as a result of abuse, cart overloading and reckless driving: “They treat them very badly, they treat them very badly.”, says Ngwevu.

When asked to compare the success of his business today to when he started using donkeys, he says that people struggle to pay for his services due to rising poverty.

Although money is hard to come by, Ngwevu lives with his grandson Phumzile Salazi who works at a local diary and the family can make ends meet.

Ngwevu uses his own routes to avoid motorists in Makhanda’s increasingly speedy roads and repairs his donkey cart himself when it gets damaged.

He hopes for more young people to learn to treat donkeys better.

AUDIO

Cart Out To Work

We all know Makhanda as a city of donkeys. These animals roam our streets at night, charm our visitors, and cause havock with our rubbish bags. But for donkey cart drivers, they are a way of earning a living. Community Journalist Brad Manaka met up with one of these drivers to find out more about his way of life.

VIDEO

MAKHANDA DRIFT

One moment you’re imagining yourself as Eluid Kipchoge about to finish a sub-two-hour marathon and the next moment you’re Indianna Jones jumping aboard a speeding horse wagon. That’s what Brad Manaka thought of this morning in Makhanda in a space of a minute. If that resembles you in any way, perhaps the community journalist’s TikTok videos are just for you!